Add your promotional text...

Did Mary Have Other Children? Did Jesus Have Siblings? – The Definitive Biblical, Patristic, and Protestant Historical Analysis

Discover the definitive study on whether Mary bore more children and if Jesus had siblings—anchored in Scripture, early Fathers, and Reformation sources.

faithfacts

4/26/202529 min read

Abstract

This article examines whether the Virgin Mary bore children other than Jesus, analyzing biblical evidence, early Christian (Patristic) testimony, and historical Protestant views. We find that while some New Testament passages mention “brothers” and “sisters” of Jesus, a closer reading and ancient context suggest these terms do not necessarily indicate other children of Mary. Early Christian writings uniformly upheld Mary’s perpetual virginity, considering the “brothers of Jesus” as either close relatives or step-siblings. The Protestant Reformers, despite rejecting many Catholic traditions, largely affirmed Mary’s perpetual virginity, in line with historic Christian teaching. Only in later centuries did many Protestant communities begin denying this doctrine, often citing a strictly literal interpretation of the biblical references to Jesus’ “brothers.” This analysis maintains that the belief in Mary’s lifelong virginity is deeply rooted in Scripture’s nuances and was universally held in Christian antiquity, remaining part of the faith of the Reformers, even if modern evangelicalism generally disputes it.

Biblical Evidence and the “Brothers” of Jesus

New Testament References to Jesus’ Brothers and Sisters

Multiple New Testament passages refer to the “brothers” and “sisters” of Jesus. The people of Nazareth, surprised at Jesus’ wisdom, asked: “Is not this the carpenter, the son of Mary, the brother of James, and Joses, and of Juda, and Simon? And are not his sisters here with us?”biblegateway.com. Likewise, Matthew 13:55–56 records the townspeople saying: “Is not His mother called Mary? And his brethren, James, and Joseph, and Simon, and Judas? And His sisters, are they not all with us?”biblegateway.com. The Gospels thus name four men (James, Joses/Joseph, Simon, and Jude) as Jesus’ “brothers,” and mention unnamed “sisters” (plural, implying at least two).

On the face of it, these verses seem to indicate that Mary had at least six other children (four sons and at least two daughters) after Jesus. Moreover, other verses casually mention Jesus’ brothers: “After this He went down to Capernaum, He, and His mother, and His brethren…” (John 2:12), and “His brethren therefore said unto Him, ‘Leave here and go to Judea…’ For neither did his brethren believe in Him.” (John 7:3-5)newadvent.orgnewadvent.org. After Jesus’ resurrection, Acts 1:14 notes that the Apostles gathered in prayer “with the women, and Mary the mother of Jesus, and with His brethren.” And Paul refers to “James, the Lord’s brother” (Galatians 1:19) when describing whom he met in Jerusalemnewadvent.org.

In addition, Matthew 1:25 is often cited in this debate. Describing Joseph’s conduct toward Mary, it says: “And [Joseph] knew her not till she had brought forth her firstborn son; and he called His name Jesus.”biblegateway.com (To “know” one’s wife is a biblical euphemism for sexual relations.) The wording “knew her not until…” has led some to conclude Joseph did know her (i.e. consummated the marriage) after Jesus’ birth. Jesus is also called Mary’s “firstborn son” (Luke 2:7), which some argue implies she had second-born and others subsequently.

Taken together, these scriptures form the primary biblical basis upon which those who answer “Yes” to the question “Did Mary have other children?” rest their case. Indeed, apart from a belief in the authority of later tradition, an average reader of the Bible would likely assume these verses mean exactly what they appear to say: that Mary and Joseph had a normal marital life after Jesus’ miraculous birth, resulting in additional children who were Jesus’ younger half-siblings. This straightforward interpretation is common in Protestant preaching today. “Everybody knew Mary had sons [and] daughters,” as John MacArthur puts it, pointing to the Gospel referencesgty.org.

The Meaning of “Brothers” (adelphoi) in Jewish Usage

A key question is what the word “brothers” (adelphoi in the Greek text) means in context. While adelphos can mean a literal sibling born of the same parents, it had a broader usage among the Hebrews and in the Bible. In the Greek Old Testament (Septuagint), adelphos translates the Hebrew ach, which denotes not only literal brothers but also relatives or even close friends. For example, Genesis 13:8 calls Abraham and his nephew Lot “brothers” (adelphoi in LXX)newadvent.org. Similarly, Jacob is called the “brother” of his uncle Laban (Genesis 29:15). This familial flexibility carried into the language of first-century Judaism.

The New Testament itself occasionally differentiates adelphos (brother) from anepsios (cousin). Colossians 4:10, for instance, refers to Mark the anepsios (cousin) of Barnabas. Thus, Greek had a specific word for “cousin.” Those who argue that Jesus’ brethren must have been His actual siblings often point out that the Gospels did not use anepsioi for Jesus’s relatives, but rather adelphoi. As an Evangelical Q&A site argues, “none of those passages uses the word anepsios (cousin)”gty.org. This is a fair observation – the New Testament authors chose the general term adelphoi. However, one must be cautious in insisting this automatically means uterine siblings. The Gospel writers, steeped in Semitic idiom and the Septuagint, often used familial terms in the traditional Jewish sense.

Notably, in the scenes at the cross, we find a “Mary the mother of James and Joses (Joseph)” distinct from Jesus’ mother (Matthew 27:56, Mark 15:40). Mark 15:40 lists “Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James the Less and of Joses, and Salome” watching the crucifixionnewadvent.org. This other Mary, mother of James and Joses, is often understood to be the wife of Clopas (Cleophas). John 19:25 clarifies that among the women at the cross was “Mary the wife of Clopas”, and calls her the “sister” of Jesus’ mother (likely sister-in-law or cousin, as it’s improbable two sisters in one family were both named Mary). If James and Joses are sons of that Mary (wife of Clopas), they are never said to be sons of the Virgin Mary in the text – only “brothers” of Jesus in a loose sense.

Early Christian historians preserved this understanding. Papias of Hierapolis, a 2nd-century bishop, listed four women named Mary in the Gospels and wrote: “Mary the mother of the Lord; Mary the wife of Cleophas, who was the mother of James the bishop and apostle, and of Simon and Thaddeus, and of one Joseph; Mary Salome, wife of Zebedee, mother of John and James; Mary Magdalene.” He then explains that “James and Judas and Joseph were sons of [Mary of Cleophas], the Lord’s aunt. James also and John were sons of another aunt [Salome]. Mary [of Cleophas] was the sister of Mary the Lord’s mother”4marksofthechurch.com. In other words, two of Jesus’ “brothers” (James the Less and Joses) were actually His cousins – sons of Mary’s sister (or sister-in-law). Likewise, Hegesippus, a 2nd-century chronicler, records that after the martyrdom of “James the Just” (known as the brother of the Lord), he was succeeded as leader of the Jerusalem church by Simon son of Clopas, “his cousin, the son of Clopas”, explicitly calling Simon “another cousin (Greek: anepsios) of the Lord”4marksofthechurch.com. These ancient testimonies confirm that the earliest Christians identified Jesus’ “brothers” as relatives – cousins or kin – not children of Mary. The very use of anepsios (“cousin”) by Hegesippus in reference to Simon suggests that by the second century there was clarity that Simon, James, Jude, etc. were not considered Mary’s own sons.

Another line of interpretation is that these “brethren” were Joseph’s children from a prior marriage. This view was strong in the Eastern Church. The Protoevangelium of James (c. 120 A.D.), an apocryphal text, relates that Joseph was an elderly widower chosen to be Mary’s guardian. It recounts that when Mary turned twelve, the priests betrothed her to Joseph, and Joseph objected, “I have children, and I am an old man, and she is young”, taking her only under protest as a ward entrusted to his care4marksofthechurch.com4marksofthechurch.com. While not Scripture, this story was highly influential. It shows that very early, Christians were uncomfortable with the idea of Mary’s virginity ending, and they explained the “brothers” as Joseph’s sons from an earlier union. In this scenario, James, Joses, Simon, and Jude were Jesus’ step-brothers, considerably older than He. Indeed, if Joseph had died by the time of Jesus’ ministry (as seems likely, since Joseph disappears from the Gospel narratives after Jesus’ childhood), these “brothers” could have assumed family responsibilities alongside Jesus. This theory also finds echo in some Western fathers (e.g. St. Epiphanius). It upholds Mary’s lifelong virginity by removing any necessity that she bore those children.

Thus, whether through the cousin theory (Jerome’s position and common in the West) or the step-sibling theory (common in the East, drawn from early tradition), early Christians found plausible explanations for the “brothers” of Jesus that do not require Mary to have given birth to other children. Both views rely on the broader semantic range of adelphos. Importantly, neither view is forced or purely apologetical; each has some biblical footing: the cousin theory leverages the multiple Marys at the Cross and known family relations, while the step-brother theory aligns with Joseph’s apparent age and the absence of any mention of these “brothers” being sons of Mary in the texts (they are never called “Mary’s sons” in Scripture). In Mark 6:3, Jesus is called “the son of Mary,” but his neighbors say “the brother of James and Joses…,” notably not “the son of Mary and Joseph” in plural. As some have pointed out, if those “brothers” were also Mary’s sons, calling Jesus the son of Mary, in singular, is oddly exclusiveeurekafirstchurch.com. This subtle point suggests the Evangelists may have been indicating that Jesus alone was Mary’s child, while those “brothers” were related in a different way.

“Until” – Does Matthew 1:25 Imply a Change?

Matthew 1:25 states Joseph “did not know her until she brought forth her firstborn son.” Does the word “until” (Greek heôs hou) imply that Joseph did know her (i.e. consummated the marriage) after Jesus’ birth? On the surface in English, it might seem so. Helvidius in 380 A.D. certainly argued that “it is clear she was known after she brought forth”newadvent.orgnewadvent.org. However, as St. Jerome and others have demonstrated, in biblical usage “until” does not automatically imply the reversal of the preceding clause once the condition is met. Jerome notes that Scripture often uses “until” or “till” to express a truth up to a certain point without implying anything about after. For example, the raven Noah sent from the ark “flew back and forth until the waters dried up” (Genesis 8:7). This doesn’t mean the raven returned after the waters dried – in fact, it never returned. 2 Samuel 6:23 says Michal, Saul’s daughter, “had no child till the day of her death.” Clearly, she did not bear a child after her death. Similarly, Jesus tells His disciples, “I am with you always, until the end of the age” (Matthew 28:20) – but no Christian thinks Christ will abandon us once the world endsnewadvent.org. “Until” in such phrases means “up to that point, and not stating anything thereafter.” It emphasizes what is true before a certain moment, without necessitating a change afterwardnewadvent.orgnewadvent.org.

Jerome put it succinctly: “Could not Matthew find words to express his meaning? ‘He knew her not,’ he says, ‘until she brought forth a son.’ He did not say he knew her afterward”newadvent.org. The purpose of Matthew 1:25 is to underscore that Jesus’s conception was absolutely virginal – Joseph had nothing to do with it. The verse’s focus is on affirming the miraculous nature of Christ’s birth, not to inform us of Joseph and Mary’s later marital relations. As Calvin observed, “No just and well-grounded inference can be drawn from these words as to what took place after the birth of Christ. He is called first-born to inform us he was born of a virgin; what took place afterward the historian does not inform us”4marksofthechurch.com4marksofthechurch.com. John Calvin even calls it “folly” to insist Matthew 1:25 must imply Mary ceased to be virgin later, saying the evangelist simply didn’t intend to address that and one should not “obstinately keep up the argument” beyond Scripture’s silence4marksofthechurch.com.

The term “firstborn son” likewise does not require later children. In Jewish law, “firstborn” status is significant regardless of whether more siblings follow – it designates the child who opens the womb (Exodus 13:2). A family’s only son is still routinely called the firstborn. Thus, calling Jesus Mary’s “firstborn” highlights His special role and Mary’s obedience to present Him at the Temple (Luke 2:22-23), not implying a second-born. As the Reformer Zwingli preached, “he [the Gospel writer] simply wished to make clear Joseph’s obedience… He had therefore never dwelt with her… And besides this, our Lord Jesus Christ is called the first-born not because there was a second or a third, but because the Gospel writer is paying regard to the precedence. Scripture speaks thus of naming the first-born whether or no there was any question of the second.”4marksofthechurch.com4marksofthechurch.com. In other words, “firstborn” is a title of honor and legal status, not a hint about later siblings.

Jesus Entrusting Mary to John: An Implicit Argument

One more biblical consideration: at the Crucifixion, Jesus, in His dying moments, entrusted His mother Mary to the Apostle John’s care: “Woman, behold thy son… Behold thy mother!” and the disciple “from that hour took her unto his own home.”biblegateway.com. This is recorded in John 19:26–27. It is significant because if Mary had other biological sons, they would normally be responsible for her care after Jesus’ death. Yet Jesus acts as if Mary has no other immediate family to turn to, placing her in John’s household. In Jewish culture, the eldest son had duty to provide for his widowed mother, but if the eldest died, that duty would pass to the next son. Jesus bypasses any such brothers and gives Mary to John, “the disciple whom He loved.” This makes the most sense if Jesus was, in fact, Mary’s only son – her “only begotten” in a sense. Early Christians like St. Irenaeus and later theologians often pointed to this scene as supporting Mary’s perpetual virginityreddit.com. It’s an implicit argument, but a strong one: Jesus would not likely have disregarded His supposed brothers (which would be a grievous slight in that culture) if they existed; nor would He deprive them of the honor of caring for their mother. The straightforward reason He entrusted Mary to John is that she had no other children to care for her. John, as a faithful disciple, became Mary’s guardian, which tradition holds he fulfilled until her assumption or dormition.

Patristic Testimony: Ever-Virgin Mary in Early Christianity

The Unanimous Early Belief in Perpetual Virginity

From the earliest centuries, Christians affirmed that Mary remained a virgin throughout her life – a doctrine often referred to as Mary’s perpetual virginity (Latin: semper virgo, “ever-virgin”). This was not a marginal or late development of medieval piety, but a widespread belief attested in the most ancient Christian writings and shared across the Church Fathers.

For roughly the first three hundred years of the Church, there was no recorded controversy on this point. The available writings simply reflect the assumption of Mary’s singular holiness and virginity. Many Fathers when mentioning Mary call her “the Virgin Mary” in contexts that imply a permanent state, not only a past event. For example, Origen of Alexandria (early 3rd century) wrote of the “brethren of Jesus” that they were not children of Mary. He cites the Protoevangelium’s narrative approvingly, noting that “according to the Gospel of Peter, the brethren of Jesus were Joseph’s children by a former wife” (the Gospel of Peter is likely a confusion with the Protoevangelium of James in Origen’s reference)4marksofthechurch.com4marksofthechurch.com. Origen accepted that Mary never had marital relations: “There is no child of Mary except Jesus, according to those who think correctly about her”, he wrote in his Commentary on John.

Likewise, St. Athanasius in the 4th century speaks of Mary as “Ever-Virgin”, and St. Epiphanius of Salamis (c. 370) explicitly defends Mary’s perpetual virginity while condemning certain heretics (the Antidicomarianites) who dared to claim Mary had normal relations after Christ’s birth. Epiphanius wrote, “We believe in one God… and in one Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God… who came down and was made man… born perfectly of the holy ever-virgin Mary by the Holy Spirit”. He lambastes those who “slur Holy Mary, the Virgin” by saying she had other children, calling such opinions heresy.

The first figure in recorded history to openly challenge Mary’s perpetual virginity was Helvidius, around A.D. 380. Helvidius wrote a tract arguing that the New Testament evidence favored Mary having a normal marriage with Joseph after Jesus’ birthnewadvent.org. He claimed that treating marriage and childbearing as something Mary would refrain from was an insult to the honorable estate of marriage, effectively placing virginity above marriage in a way he thought unbiblical. In response to Helvidius, St. Jerome, the great biblical scholar, wrote “Against Helvidius: On the Perpetual Virginity of Mary” (c. 383). Jerome’s treatise thoroughly dismantled Helvidius’s points and became the definitive patristic argument for Mary’s lifelong virginity. Jerome shows fiery indignation at Helvidius’s novelty, calling him an “ignorant boor who has scarcely learned his first lessons”newadvent.org. He notes that Helvidius relied on the earlier writer Tertullian (who in the late 2nd century had hinted Mary may have had other children) – but Jerome somewhat dismisses Tertullian on this point since Tertullian later veered into Montanist heresy and is not revered as a “Father” in the Church. Jerome also mentions a certain Victorinus who might have held a similar opinion as Helvidius, but essentially Jerome treats Helvidius’s view as an aberration against the received teaching of the Church.

In Against Helvidius, Jerome systematically argues: (1) Joseph and Mary’s marriage was real but Joseph was more a protective guardian – Joseph is “putative” husband, not that he ever carnally knew Marynewadvent.org. (2) The “brothers” of the Lord are cousins or close kin. Citing the Gospel accounts at the cross, Jerome identifies James, Joses, Jude, and Simon with the children of Mary of Clopas (whom he assumes to be the Virgin’s sister)newadvent.orgnewadvent.org. He appeals to earlier writers (likely Papias, Origen, etc.) to back up this identificationnewadvent.org. (3) Jerome then defends the superiority of virginity dedicated to God over the married state (a view widely held in his era), to show there is no indignity in Mary remaining always virgin – in fact, it befits her unique role. In doing so, Jerome incidentally testifies that not only Mary, but Joseph also, preserved virginity in their marriagenewadvent.org, a belief shared by many Fathers (the idea that Joseph was a lifelong chaste widower).

Jerome’s counter-arguments became classic. For instance, regarding Matthew 1:25, Jerome marshals many scriptural examples of “until” that do not imply a later changenewadvent.orgnewadvent.org, as we discussed earlier. He even uses a bit of sarcasm, saying: “Did Joseph, in your view, impatiently desire to defile the virgin whom God’s angel had sanctified? If he “knew her not until she brought forth” – did he rush to ‘know’ her afterward? The Gospel is affirming the miracle, not what happened later.” Jerome notes that if we take “until” to always imply a reversal after the fact, we would absurdly conclude that, e.g., God ceased to be God after old age (in Isaiah 46:4) or that Christ’s presence would vanish after the end of the worldnewadvent.orgnewadvent.org. His tone in the treatise shows that by the late 4th century the perpetual virginity of Mary was so entrenched in orthodoxy that to deny it was seen as slandering the holy family and misreading Scripture.

After Jerome’s forceful defense, Helvidius’s view was effectively stamped out in mainstream Christianity. Another opponent of Mary’s perpetual virginity was Jovinian, around the same time, who argued that virginity held no spiritual superiority over marriage and as part of his thesis claimed Mary did not remain virgin (to assert that motherhood and virginity are equal honors). He too was rebutted (by St. Jerome and others like St. Ambrose and St. Augustine). The Church Father consensus thereafter is clearly that Mary never had other children. St. Augustine (early 5th century) wrote, “Mary remained a virgin in conceiving Jesus, a virgin in giving birth to Him, a virgin in carrying Him, a virgin in nursing Him at her breast – always a virgin”. The phrase “ever-virgin” (aeiparthenos in Greek) appears routinely. By the time of the Second Council of Constantinople in 553, an ecumenical council, it could actually use “Mary, Ever-Virgin” as a given title in its documentsen.wikipedia.org, indicating this doctrine was considered part of the Church’s faith.

In summary, the Patristic testimony overwhelmingly answers: No, Mary had no other children; Jesus was her only son. The “brethren of the Lord” are explained through kinship ties or Joseph’s prior family. The early Christians saw Mary as the Ark of the New Covenant – a sacred vessel of Christ – and found it unfitting that she would afterward engage in ordinary sexual relations. Even Protestant historians admit that the perpetual virginity of Mary was “rarely challenged” before the Reformationcatholic.comen.wikipedia.org. It was a point of unity among Catholics, Orthodox, and indeed the magisterial Reformers.

Protestant Historical Perspectives

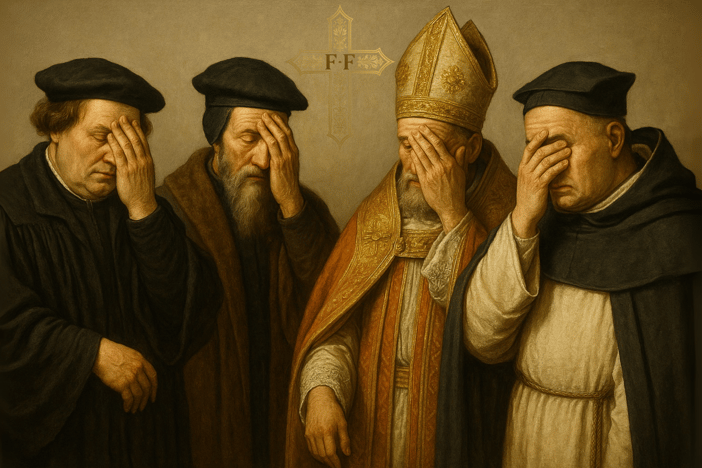

Magisterial Reformers: Luther, Calvin, Zwingli on Mary’s Virginity

It may surprise some modern Protestants that the leaders of the Reformation themselves upheld the perpetual virginity of Mary. Martin Luther, John Calvin, Huldrych Zwingli, and later Protestant scholastics all affirmed the traditional view that Mary had no children aside from Jesus. They did so not out of any desire to placate Catholic sensibilities, but because they found it biblically sound and inherited it as part of historic Christian orthodoxy.

Martin Luther (1483–1546), who had a deep devotion to Mary early in his life and retained great respect for her, vigorously defended her perpetual virginity even after breaking from Rome. In a 1523 treatise against some radicals, Luther wrote: “A new lie about me is being circulated, that I am saying Mary had more children after Jesus…I have never preached or written such a thing!” (This indicates some rumor accused him of Helvidius’s view, which he denied.) In his 1537 Smalcald Articles – a Lutheran confession of faith – Luther implicitly included Mary’s perpetual virginity by referring to Christ’s birth “from the ever-virgin Mary.” Luther’s sermons and writings repeatedly state Mary remained a virgin. He commented on John 19:26 that Jesus entrusted Mary to John precisely because “she had no other children”. On Matthew 1:25, Luther said the text “simply says [Joseph] knew her not until she brought forth her firstborn son. This does not imply he later did; Scripture just doesn’t say so… He never did know her. This babble [that Mary had other children] is without justification.”4marksofthechurch.com. Furthermore, Luther argued that “‘brothers’ really means ‘cousins’ in this context, for Holy Writ and the Jews always call cousins brothers”4marksofthechurch.com. He cites the same kind of Old Testament patterns we discussed. In sum, Luther had no hesitation calling Mary “ever-virgin.” In one of his sermons he even wrote: “Christ, our Savior, was the real and natural fruit of Mary’s virginal womb… and she remained a virgin after that.”4marksofthechurch.com.

John Calvin (1509–1564) likewise believed in Mary’s perpetual virginity, though he was more cautious in how he discussed it, concerned not to go beyond Scripture. When the Helvidian interpretation of Matthew 1:25 re-emerged in Calvin’s time, Calvin strongly condemned it. In his commentary on Matthew, Calvin wrote: “Helvidius has shown himself ignorant by saying that Mary had other sons… The inference that Joseph knew her after the birth is illogical. The Evangelist did not mean that. He meant Joseph had no relations with her at all up to her delivery.”4marksofthechurch.com4marksofthechurch.com. Calvin emphasized that nothing was recorded about Mary having later children, and “no man will persist in this argument unless he is pig-headed and foolish”4marksofthechurch.com. He also noted the broad use of “brethren” among Hebrews: “Under the word ‘brethren’ the Hebrews include all cousins and other relations.”4marksofthechurch.com. Therefore, the Gospel writers calling some men “Jesus’ brothers” did not prove they shared the Virgin’s womb. Calvin did stop short of making Mary’s perpetual virginity an article of faith – he felt it was not explicitly a fundamental doctrine and that one shouldn’t be too dogmatic where Scripture is silent. But personally he was convinced of it and severely reproached those who denied it, out of a concern for reverence toward Christ and His mother. He saw no motivation to assume Mary’s virginity was later compromised.

Huldrych Zwingli (1484–1531), the Reformer of Zurich, was perhaps the most emphatic of the three on this topic. He wrote a sermon in 1522 specifically titled “The Perpetual Virginity of Mary”, in which he extolled Mary and vigorously defended her virginity before, during, and after Jesus’ birth. Zwingli wrote, “To deny that Mary remained ‘inviolate’ before, during and after the birth of her Son is to doubt the omnipotence of God.”4marksofthechurch.com. He praised Mary as “ever chaste, immaculate Virgin Mary”4marksofthechurch.com and said, “I believe with all my heart… that she remained a pure and unsullied virgin after the birth of Christ for eternity.”4marksofthechurch.com. Zwingli even used Mary’s perpetual virginity as an example of God’s miraculous power and a model of holy purity. He reportedly had the phrase “ever virgin” inscribed in a liturgical book and noted that he “preached Mary ever-virgin in Zurich”. It is clear he would brook no disrespect toward the mother of the Lord. Notably, Zwingli and Luther both taught that Mary’s virginity in childbirth was miraculously preserved (the doctrine of virginitas in partu – that Jesus was born without violating Mary’s physical virginity). This goes beyond our scope, but it further underscores how highly they regarded Mary’s unique role.

Other Reformation-era figures agreed. Heinrich Bullinger (Zwingli’s successor, author of the Second Helvetic Confession) affirmed Mary’s perpetual virginity in that influential creed: Christ was “born of the ever virgin Mary”ccel.org. The Geneva Bible (1560), an early English Calvinist translation, included marginal notes upholding Mary’s perpetual virginity. John Wycliffe (a 14th-century proto-reformer) held that Mary remained a virgin. Even John Wesley (1703–1791), the Anglican priest who founded Methodism, in a letter wrote of “the blessed Virgin Mary, who, as well after as before she brought [Jesus] forth, continued a pure and unspotted virgin”crossingthebosporus.wordpress.com. Thus, across the spectrum, the leaders of Protestantism’s first two centuries maintained this doctrine. They did not see it as “Romish” but as an integral part of the Christian understanding of Jesus and Mary.

Why did the Reformers cling to this teaching, even as they discarded other Marian doctrines like her intercessory role or the Immaculate Conception? Two main reasons emerge:

Biblical Conviction: They found no compelling biblical reason to deny Mary’s perpetual virginity, and they saw plausible biblical harmony in affirming it (as shown by their exegesis of “brothers” and “until”). Since it had been taught by the early Church and did not contradict Scripture, they accepted it. They were sola scriptura Protestants, but sola scriptura does not mean nuda scriptura (Scripture stripped of all traditional understanding). Where the weight of historic Christian witness was strong and Scripture allowed it, they were inclined to maintain continuity.

Christological Implications: Some Reformers hinted that denying Mary’s perpetual virginity could subtly demean Christ’s uniqueness. For example, a few ancient heretics who denied Jesus’ full divinity also disliked exalted claims about Mary. The Reformers, staunch defenders of Christ’s deity, saw Mary’s perpetual virginity as a safeguard of the doctrine of Incarnation – a sign that Jesus’ birth was absolutely singular and sacred. Theodore Beza, Calvin’s successor, even listed Mary’s perpetual virginity as one of the doctrines Protestants agree on with Catholics, seeing it as supporting the truth of Christ’s Incarnationen.wikipedia.org. Zwingli’s comment about doubting God’s omnipotence suggests he viewed Mary’s ever-virginity as highlighting God’s miraculous power in the Incarnation and nativity of Christ.

In any case, by the end of the 16th century, virtually all major Protestant confessions still either explicitly affirmed Mary’s perpetual virginity or did nothing to counter it (simply assuming the ancient understanding). The Anglican tradition’s foundational document, the 39 Articles (1563), is silent on Mary’s perpetual virginity, neither affirming nor denying it – but Anglican divines commonly believed it. For instance, the Anglican Bishop Lancelot Andrewes (1555–1626) spoke of “the Virgin Mary, ever virgin”. Lutheran orthodoxy likewise continued to hold it as a pious belief (it was referenced in the Formula of Concord’s Epitome). The Second Helvetic Confession mentioned above made it part of Reformed confessional teachingccel.org. There was essentially no disagreement among Catholics, Lutherans, Reformed, or Anglicans on this point in the 1500s – an ironic fact given later divisions.

Later Protestant Changes: The Post-Reformation Shift

Over time, however, certain Protestant groups began to revisit this doctrine and question it. The shift did not happen overnight, but by the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, as Protestantism further distanced itself from anything seen as “Catholic tradition,” the perpetual virginity of Mary came under skepticism. A rationalist streak in the Enlightenment era, combined with a growing emphasis on “Scripture alone” in its most literal sense, led many Protestant teachers to simply take the New Testament references to Jesus’ brothers at face value and drop the older explanations.

It’s worth noting that the Anabaptists (radical reformers of the 16th century) were among the first who might have rejected Mary’s perpetual virginity, but even there it’s not monolithic. Interestingly, one prominent Anabaptist, Balthasar Hubmaier, actually maintained belief in Mary’s perpetual virginity and called her Theotokos (Mother of God) in his writingsen.wikipedia.org. So the earliest breakaway sects didn’t uniformly reject it either.

The real change became evident by the 18th-19th centuries in popular Protestant thought. John Wesley stands as an exception in the 18th century (being an Anglican-Methodist who upheld the doctrinecrossingthebosporus.wordpress.com), but many of his Methodist followers in subsequent generations did not transmit that teaching. By the 19th century, among Evangelicals and Baptists, the idea of Mary having other children was commonly assumed, and the perpetual virginity was viewed with suspicion as an accretion of non-biblical tradition. This coincided with a general trend: Protestants were defining themselves increasingly in contrast to Roman Catholicism, so doctrines with no direct impact on salvation that appeared “Catholic” were often dropped or ignored.

In the modern era, most Evangelical, Pentecostal, and Baptist churches teach (or take for granted) that Mary and Joseph had a normal marriage after Jesus was born. For example, the Baptist Faith and Message 2000, an official Southern Baptist confession, simply states that Jesus “was… born of the virgin Mary.”oncedelivered.net After that singular event of the virgin birth, it makes no mention of Mary’s continued virginity – implicitly leaving it aside. The prevailing attitude is that since Scripture doesn’t explicitly teach perpetual virginity, one need not hold it; and the references to Jesus’ siblings are interpreted in the most straightforward, literal way (as younger half-siblings). It’s often pointed out that the simplest reading of Matthew 1:25 (“did not know her until…”) would suggest a change afterward – even though, as we have shown, that is not the only possible reading, it is the one most modern Protestants adopt.

Modern Protestant Bible commentaries often include remarks like: “Mary remained a virgin until the birth of Jesus, after which she had other children with Joseph, as implied by terms ‘firstborn’ and ‘until’ and by passages naming Jesus’ brothers and sisters.” Such statements are found in study Bibles and evangelical commentaries. They reflect the contemporary consensus outside liturgical Protestant traditions.

Notably, conservative evangelical scholars see no theological need for Mary to have remained a virgin. Since Protestant theology (aside from the Anglicans and some high-church Lutherans) generally does not attribute a special sacral status to virginity or to Mary’s person beyond bearing Christ, the perpetual virginity is viewed as an unnecessary doctrine. In fact, some argue that insisting on Mary’s perpetual virginity could downplay the goodness of marital sex and family – a concern Helvidius originally raised. Protestant apologist James White, for instance, has argued that there would have been nothing wrong or impure about Mary and Joseph coming together in marriage after Jesus’ birth, and that to suggest otherwise is to import extrabiblical ascetic ideas.

However, it should be remembered that some Protestants have never abandoned the doctrine. Certain Anglicans and Lutherans, especially of the high-church variety, continue to refer to Mary as Ever-Virgin in their liturgies and teachingsen.wikipedia.org. For example, the historic Anglican prayer books call Mary “ever-Virgin” in some prayers. The Eastern Orthodox (who are not Protestant, but non-Catholic) and the Oriental Orthodox have unwaveringly upheld perpetual virginity from the beginningen.wikipedia.org. So the belief is by no means only “Roman Catholic.” In recent years, even a few evangelical voices have re-examined the question. There is a minor trend of Protestant theologians and authors reconsidering Mary’s role, with some concluding that the perpetual virginity is both credible and edifying. They argue that acknowledging it can enrich Christology and our appreciation of the Incarnation. These remain a minority in evangelicalism, but their work shows the question is not entirely closed. One Protestant writer titled his article, “The Perpetual Virginity of Mary: Why I Changed My Mind,” indicating a personal journey from the common evangelical view to the historic oneconciliarpost.com.

Nonetheless, the dominant Protestant view today is encapsulated by the quote from GotQuestions: “The idea of the perpetual virginity of Mary is unbiblical.”gotquestions.org Many Protestants see it as a dogma that arose from extrabiblical tradition and possibly from an over-exaltation of Mary, which they are keen to avoid. In polemical contexts, some even use the existence of Jesus’ “brothers” to counter Catholic doctrines about Mary (for example, “See, the Bible refutes Mary’s perpetual virginity and thus, by extension, casts doubt on Catholic Marian teachings.”).

Conclusion

Did Mary have other children? According to the vast consensus of Christian belief for 1500 years – and supported by interpretations of Scripture and early historical evidence – the answer is No: Jesus Christ was the only child ever borne by the Virgin Mary. The so-called “brothers” and “sisters” of the Lord are best understood as His cousins or kin (or possibly step-siblings through Joseph). The Bible, when read in context and alongside ancient usage, does not require us to conclude Mary’s womb brought forth any child save Jesus. In fact, subtle details like Jesus being called the son of Marybiblegateway.com, and His action from the Cross entrusting Mary to Johnbiblegateway.com, support the traditional position that Mary remained a virgin and had no other biological children.

The Patristic evidence is unanimous and unequivocal in upholding Mary’s perpetual virginity. From the second century through the fourth and beyond, Christian bishops and scholars taught that Mary was “ever-virgin.” When a few challenged this, the Church rebutted them firmly, seeing the doctrine as protective of Christ’s miraculous Incarnation and of Mary’s special sanctity as the one who bore God in the flesh. Mary’s virginity was likened to the sealed gate in Ezekiel’s vision (Ezekiel 44:2 – “the gate that shall remain shut… no man shall enter by it, because the Lord, the God of Israel, has entered by it” – a verse early Christians saw as a prophecy of Mary’s perpetual virginity). Such was the reverence the early Church had for the mystery of God becoming man in the womb of the Virgin that they could not countenance that womb bearing another ordinary child.

The Protestant Reformers, contrary to what many think today, did not reform or jettison this particular doctrine. They embraced it – not to exalt Mary for her own sake, but to emphasize the singular glory of Christ. Luther, Calvin, Zwingli, Cranmer, Wesley and others testify that one can be thoroughly biblical, Christ-centric, and still affirm Mary’s perpetual virginity. They did so because they read Scripture in line with historic Christian understanding and found no conflict.

It has only been in later centuries that most Protestants parted ways with this aspect of historic Christianity. This shift largely stemmed from rejecting any teaching not plainly spelled out in Scripture and from a desire to distance Protestant faith from Marian devotion extremes. Yet, as we have seen, Scripture is not as plain as it might seem at first glance on this question – and the earliest Christians very close to the apostles’ time interpreted those Scriptures in a way entirely consistent with Mary having no other children.

For Catholics and Eastern Orthodox today, Mary’s perpetual virginity remains a cherished doctrine, integrated into their understanding of who Jesus is (the absolutely unique Son of Mary and Son of God) and who Mary is (the ever-virgin Mother of God). For Protestants, it is a point of debate and often disagreement. But given the evidence from Scripture’s context and the overwhelming historical witness, there is room for Protestant believers to reconsider this teaching without compromising biblical integrity. As one Protestant author candidly reflected, once he studied the issue he could “find no scriptural warrant for insisting that Mary did have other children”, and much to suggest she didn’t.

In the end, whether one personally accepts Mary’s perpetual virginity or not, it should be approached with care and respect. It is not a matter of salvation, but it does touch on our appreciation of the Incarnation and the holiness of God’s work. The doctrine developed not to glorify Mary independently, but to protect the dignity of Christ’s birth and to honor the vessel chosen for that miraculous event. Even the reformers understood that. Mary’s perpetual virginity stands as a sign: a sign of the Lord’s singular entrance into the world. As Zwingli wrote, “He [Christ] was brought forth from a most chaste virgin, inviolate. To think otherwise… what folly this is!”4marksofthechurch.com.

Thus, the weight of biblical and historical evidence leans in favor of Mary having no other children besides Jesus. While modern interpretations vary, the enduring Christian testimony – across time and confessions – compellingly testifies that the mother of Jesus remained ever-Virgin, consecrated wholly to her divine Son. Mary’s unique role in salvation history was fittingly matched by a unique grace of virginity kept intact, a view shared by the early Church and even by the initial Protestants. It is a beautiful consensus of the first 1500 years of Christianity, one that today’s Christians can rediscover and appreciate as part of the fullness of the faith.

Executive Summary

Biblical References – “Brothers of Jesus”: Several Gospel passages refer to Jesus’ “brothers” (e.g. “James, Joses, Judas, and Simon”biblegateway.combiblegateway.com) and “sisters.” Many readers assume this means Mary had other children. Also, Matthew 1:25 says Joseph “knew her not till she had brought forth her firstborn son”biblegateway.com, which some take to imply Joseph and Mary had normal marital relations afterward. We will examine how terms like adelphoi (“brothers”) were used in the Bible and address the meaning of “until” in Matthew 1:25.

Interpretation in Context: In Jewish and scriptural usage, “brothers” can mean not only literal siblings but also extended kin. For example, Abraham called his nephew Lot “brother”newadvent.org. Early Christian witnesses noted that multiple individuals called Jesus’ “brothers” in Scripture were actually sons of another woman named Mary (Mary of Clopas), likely a relative of Jesus’ mother4marksofthechurch.comnewadvent.org. Thus, these “brothers of Jesus” could be cousins or kin. Another ancient tradition holds they were Joseph’s children from a prior marriage (step-siblings of Jesus), preserving Mary’s own virginity. The second-century Protoevangelium of James depicts Joseph as an older widower chosen to guard Mary, explicitly stating, “I have children, and I am an old man, and she is a young girl”4marksofthechurch.com, implying Mary remained a consecrated virgin and that Jesus’ “brothers” were Joseph’s children by his former wife4marksofthechurch.com.

Early Church Teaching: Early Christians uniformly taught Mary’s perpetual virginity – that she remained ever-virgin before, during, and after Christ’s birth. Church Fathers like St. Jerome refuted the claim that Mary had other children as a heretical novelty introduced by one Helvidius around A.D. 380newadvent.org. Jerome argued from Scripture that references to Jesus’ brothers meant cousins or step-siblings, not children of Marynewadvent.org. He noted that the same names of “brothers” (James, Joses, etc.) appear in the Gospels as sons of “the other Mary” (Mary of Clopas) at the cross, not of the Virgin Marynewadvent.org. He also explained that Matthew 1:25’s phrase “[Joseph] knew her not until she brought forth a son” does not imply a change afterward, citing numerous biblical examples where “until” (Greek: heôs) denotes no change after the factnewadvent.orgnewadvent.org. For instance, “God says, even to your old age I am He” – God doesn’t cease to be God after old agenewadvent.org. Likewise, “Joseph knew her not until Jesus’ birth” means he had no marital relations with Mary up to that point, with no implication that he ever did afternewadvent.orgnewadvent.org. This interpretation was already supported by earlier Christian writers and became the consensus of the Church. By the late 4th century, a Church council (Second Council of Constantinople, 553) even formally honored Mary with the title Aeiparthenos, “ever-virgin.” The belief that Mary bore no other children was thus a standard part of Christian doctrine in both East and West.

Protestant Reformers’ View: The founders of Protestantism in the 16th century – Martin Luther, Huldrych Zwingli, John Calvin, and even later figures like John Wesley – accepted Mary’s perpetual virginity as historic Christian truth. They broke with Rome on many points but not on this teaching. “Christ… was born of a most undefiled Virgin and she remained a virgin after that,” affirmed Martin Luther4marksofthechurch.com. He vigorously rejected any suggestion that Mary had other children, calling arguments to the contrary “babble… without justification”4marksofthechurch.com and pointing out that ‘brothers’ in Scripture could mean cousins4marksofthechurch.com. John Calvin likewise denounced those like Helvidius who argued Mary had several sons as “ignorant”, insisting that nothing in Matthew 1:25 or elsewhere warrants the claim that Mary’s virginity ceased after Jesus’ birth4marksofthechurch.com4marksofthechurch.com. Calvin cautioned that Scripture does not detail Mary’s life afterward and “no man will obstinately keep up the argument [that Mary had other children], except from an extreme fondness for disputation”4marksofthechurch.com. Zwingli was even more emphatic, stating, “I firmly believe that [Mary], having borne for us the Son of God, remained a pure and unsullied virgin after the birth, for all eternity”4marksofthechurch.com4marksofthechurch.com. He warned that denying this was equivalent to doubting God’s omnipotence4marksofthechurch.com. The Second Helvetic Confession (1562), a major Reformed creed by Heinrich Bullinger, explicitly names Mary as the “ever virgin Mary” in its article on Christ’s incarnationccel.org. And in the 18th century, John Wesley (founder of Methodism) wrote that Mary “as well after as before [Jesus] brought Him forth, continued a pure and unspotted virgin”crossingthebosporus.wordpress.com. Clearly, the early Protestants maintained continuity with the ancient Church on this point.

Modern Protestant Stance: In contrast, many modern Protestant denominations and theologians have abandoned the perpetual virginity of Mary. Emphasizing sola scriptura (Scripture alone) and a more literal reading of the New Testament, they argue that the plain sense of “brothers and sisters” of Jesus indicates Mary had other natural children. For example, evangelical teacher John MacArthur states bluntly: “Everybody knew Mary had sons [and] daughters. John 7 talks about Jesus’ brothers not believing in Him.” He dismisses the Catholic explanation that these were cousins, noting that the Greek word for cousin (anepsios) is not used in those passagesgty.org. Likewise, the popular Baptist resource GotQuestions asserts, “Mary was a virgin when she gave birth to Jesus… but she was not a virgin permanently. The idea of the perpetual virginity of Mary is unbiblical.”gotquestions.org. Most evangelical Protestants today concur, treating the doctrine as a later Catholic development unsupported by clear Bible verses. Notably, no major contemporary Protestant confession of faith affirms Mary’s perpetual virginity; they typically affirm the virgin birth of Christ but remain silent about Mary’s status afterward. This silence has generally been interpreted as permitting the belief that Mary and Joseph had a normal marriage after Jesus’ birth, even though the Reformers themselves did not teach this.

Learn More

Follow @portalfaithfacts or visit www.faithfacts.portaljmj.com for more myth-busting and truth-grounded insights on Christian faith and history.

👉 Liked this content?

🔍 Follow @portalfaithfacts for more facts and myth-busting insights on Christian faith and Church history! 🧠 Real faith is even stronger when it's grounded in truth.

Sources:

The Holy Bible, New Testament (Matthew 1:25; Mark 6:3; Matthew 13:55–56; John 19:26–27, etc.)biblegateway.combiblegateway.combiblegateway.combiblegateway.com

Papias of Hierapolis, Exposition of the Sayings of the Lord (Fragment X) – as quoted by ancient sources4marksofthechurch.com.

Hegesippus, Memoirs (Hypomnemata), fragment on the relatives of Jesus4marksofthechurch.com.

Protoevangelium of James (apocryphal gospel, c. 2nd century)4marksofthechurch.com4marksofthechurch.com.

St. Jerome, Against Helvidius: The Perpetual Virginity of Mary (A.D. 383)newadvent.orgnewadvent.org.

St. Augustine, Sermons and De Virginitate – (affirming Mary’s lifelong virginity).

Second Council of Constantinople (553), Canon 2 (refers to Mary as ever-virgin)en.wikipedia.org.

Martin Luther, Sermons on John (1537) in Luther’s Works, vol. 22 (on John 1–4) – quotes on Mary’s virginity4marksofthechurch.com4marksofthechurch.com.

Martin Luther, That Jesus Christ Was Born a Jew (1523) – denial of any teaching that Mary had other children4marksofthechurch.com.

John Calvin, Commentary on Matthew, Mark, and Luke (Harmonia) – remarks on Matthew 1:25 and 13:554marksofthechurch.com4marksofthechurch.com.

Huldrych Zwingli, Sermon on “Mary, ever virgin, Mother of God” (1522) – various quotes4marksofthechurch.com4marksofthechurch.com.

Second Helvetic Confession (1562) by Bullinger, Chapter XI (Incarnation) – “born of the ever virgin Mary”ccel.org.

John Wesley, Letter to a Roman Catholic (18th c.) – “Mary… continued a pure and unspotted virgin”crossingthebosporus.wordpress.com.

John MacArthur, “Exposing the Idolatry of Mary Worship” (sermon, Grace to You) – critique stating Mary had other childrengty.org.

GotQuestions Ministries, “What does the Bible say about the virgin Mary?” – evangelical standpoint denying perpetual virginitygotquestions.org.